Why bank stocks look risky in a tricky market

During the past decade, we have experienced a low growth and low interest rate environment globally. This has pushed income seeking investors up the risk curve in search for income. The big four Australian banks have attracted many income seeking investors, offering some of the highest dividend yields in the world.

By Adam Spicer

During the past decade, we have experienced a low growth and low interest rate environment globally. This has pushed income seeking investors up the risk curve in search for income. The big four Australian banks have attracted many income seeking investors, offering some of the highest dividend yields in the world.

However, in light of the current backdrop, the data supports the notion that the biggest risks facing the Australian banks are our unsustainable house prices, coupled with record household debt. The flow-through effect that housing has on the economy is quite profound, and it is on this basis that we are underweight the Australian banks.

It also applies to the domestic sectors challenged by a sluggish demand outlook, intensifying competition and structural or regulatory change, including retail and housing related sectors. This leads us to favour international equities, and Australian listed companies with globally leading businesses/offshore earnings.

The flow-through effect that housing has on the economy is profound, and it is on this basis that we are underweight the Australian banks

The Australian equity market, whilst trailing the US, has performed surprisingly well over the past year, outperforming other major markets. Indeed, the S&P 500 is up around 16.4 per cent whilst the ASX200 has gained approximately 6.8 per cent. Looking ahead, however, we see four key reasons why investors should consider diversifying away from the Australian market and including international equities in their asset allocation:

- Earnings momentum has probably peaked. The recent Australian earnings reporting season for FY18 delivered profit growth of about 7 per cent YoY. The key driver was large gains in resources profits (up around 25 per cent YoY), driven by higher oil and base metals prices. Consumer-facing domestic sectors saw modest profit growth, held back by sluggish top-line sales growth. Earnings estimates for the year ahead were revised down by a modest 0.2 per cent in August, the first month-on-month decline in more than a year.

- Company earnings may come under downward pressure as downside risks to the Australian economy rise. Home prices down 2.9 per cent YoY, while auction clearance rates have fallen from about 80 per cent into the mid-50s percentage level. Both falling prices and turnover should slow realised capital gains in housing, lifting the savings rate from an unsustainable 1 per cent, and slowing consumer spending. Home prices are a dominant 55 per cent share of household wealth. As such, the home price boom has been a key driver of the strong “wealth effect” observed in recent years, with the household savings ratio falling from 8-9 per cent in 2011-12 to around 1 per cent currently.

- Elevated levels of political risk in Australia, with the ALP on track to win in a landslide victory, which has not yet been discounted into the market. Four policies for investors to consider:

-

- Ending of negative gearing on established properties.

- Halving the capital gains discount from 50 per cent to 25 per cent.

- Ending excess franking credit refunds for most investors, a challenge for older Australians not on the pension.

- Minimum 30 per cent tax on discretionary trust distributions, a challenge for the estimated 1 million small businesses and $590 billion of assets in such trusts.

With the backdrop of 11 consecutive budget deficits without a recession, the highest national debt in modern times, an increasingly large and intrusive government sector, a shift to the left is likely to continue these trends, further slowing productivity growth and Australia’s potential GDP growth.

-

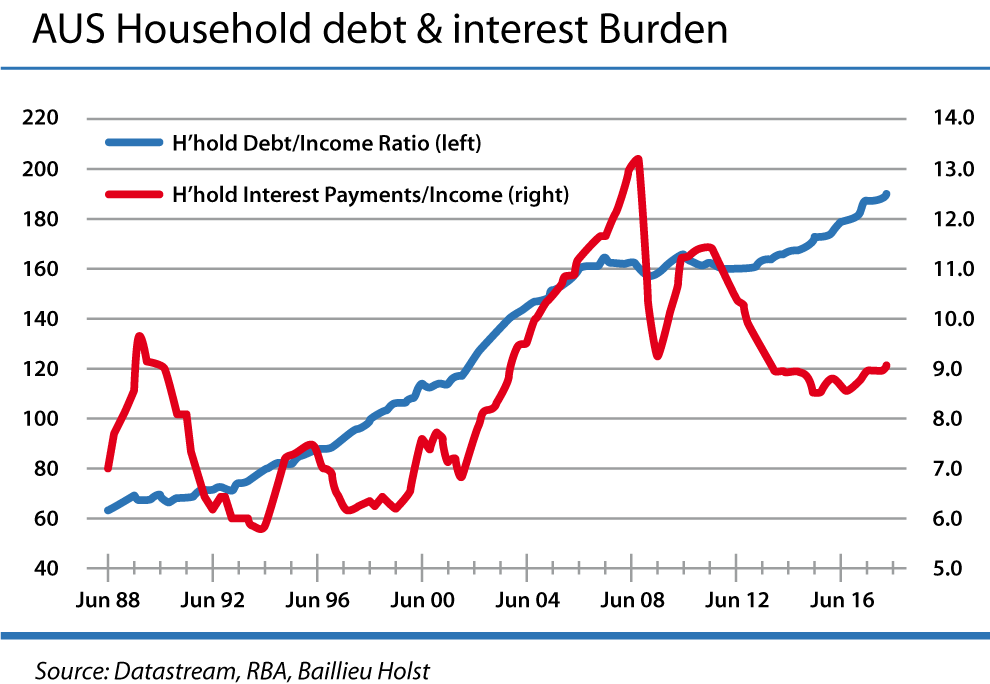

- Structurally lower interest rates than the US, reflected in Australia’s 190 per cent household debt ratio.

In our view, the fall of Australian interest rates below the US level is not just cyclical, but structural. Australian household debt at more than 190 per cent of income presently is almost twice US levels at 99 per cent. Even with record low cash rates, Australia’s interest burden is at an above average 9.0 per cent of household income. On our estimates, to lift cash rates back to 3.0 per cent, well below the long-term pre-GFC average of 5.6 per cent, would lift the interest burden to 11.5 per cent of household income, a level only ever exceeded in 2007-08.

Adam Spicer is Financial Adviser at Baillieu Holst

comments