Spying for Shin Bet

ISRAELI director Nadav Schirman’s intriguing documentary, The Green Prince, is about a 17-year-old Palestinian cultivated as a spy for the Israeli security service Shin Bet, and the improbable friendship that developed over many years between the spy and his handler, Gonen Ben-Itzhak.

Schirman’s direction of The Green Prince, which opened in Australian cinemas on December 4, is masterly and the tale it tells is deeply psychological.

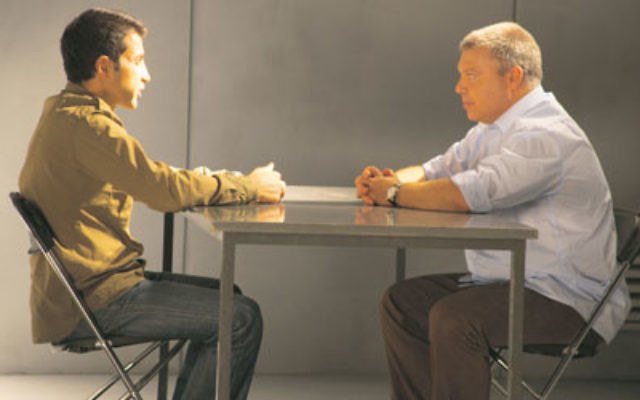

Made over a period of six years, The Green Prince is structured much like a Shin Bet interrogation, with teenager Mosab Hassan Yousef and his handler Ben-Itzhak filmed in a confined space, having nowhere to look but into the eye of the camera, which in many ways acts as a truth detector.

More questions are raised than answered, and the chance to discuss some of these with Schirman was irresistible when the filmmaker was in Melbourne last month for the Jewish International Film Festival where the film was screened.

Yousef was born in Ramallah in 1978, and worked undercover for the Shin Bet from 1997 to 2007. During this time he prevented dozens of assassinations and suicide attacks, exposed Hamas cells, and helped Israel hunt down many militants, including his own father Sheikh Hassan Yousef, a co-founder of Hamas and one of its most charismatic leaders.

As his father’s eldest son, Yousef was the heir apparent to “royalty”. He grew up wanting to be a fighter and was arrested when he was 10 for throwing rocks at Israeli settlers during the First Intifada (1987-1993). He was subsequently arrested and jailed many times, before being imprisoned in 1996 for purchasing illegal weapons.

It was during this period of confinement and interrogation by Ben-Itzhak that Yousef was “turned” and persuaded to betray his father, the Palestinian cause, and everything he believed in. How did this happen?

Shin Bet’s codename for Yousef was the “green prince”. Green is a traditional Islamic colour. It was supposedly the colour of Muhammad’s cloak and is the colour of the Hamas flag. It also has resonance as a measure of Yousef’s youthfulness when he fell into the hands of the Shin Bet, his capacity to grow from a green shoot into a fully-formed spy.

The key to any successful recruitment is the spymaster’s skill at handling or manipulating his prey. According to Schirman, Ben-Itzhak was a master of “the game”, and Schirman should know. In many ways his filmmaking uses similar techniques and psychology, and when I suggest to him that in this sense a filmmaker can be seen as not just a spy with a camera but as a spy handler as well, he agrees with me.

“That’s exactly what Gonen said. When we’d finished shooting, he came up to me and said: ‘You know Nadav, this is the first time that I felt like I was being handled!’ It’s incredible, because it’s only then that you see the similarities,” he says.

“But we only spy on people’s emotions. There’s three ways of gathering intelligence, and we show all three levels in the film.

“There’s visual intelligence (VISIN) or the use of drones and security cameras. Then signal intelligence (SIGINT) which is what NSA does in the USA, like capturing your emails and listening in to your phone conversations.

“Then you have human intelligence. This is the most fragile but also the most crucial of all, because you can’t interpret the SIGINT and VISIN if you don’t have the human,” Schirman says.

“And human intelligence is very much about emotions. You need to understand emotions to know your intentions and the intentions of others.”

More than anything else, Schirman insists that his film is not about spies but relationships. At the heart of the film is the bond that develops between the spy and his handler which transcends national and religious boundaries and finds common ground in compassion and concern.

Ben-Itzhak grew close to his operative and was seen as betraying the Shin Bet by breaking protocol and becoming his friend, meeting him alone and permitting him holiday time.

For this, Ben-Itzhak was fired despite having worked for the agency for 10 years. And Yousef – unable to work with other handlers, and having undergone a total realignment of his values and understanding about who he was and what he wanted – rejected his past life, became a non-denominational Christian, and today lives in semi-seclusion in the United States.

A key turning point for Yousef is revealed early in the film, recounted in one of the talking-head sequences which dominate the film’s narrative, almost lost in the ongoing monologue as the viewer strains to listen and understand.

Yousef explains that during his incarceration in the Hamas section of the prison, he came face to face with Hamas’s treatment of their own.

The organisation that his father was prepared to die for tortured hundreds of prisoners (for reasons not elaborated upon in the film) and got away with this by making a noise or turning up music loudly so that no one could hear.

Compared with his own treatment in prison and by the Shin Bet, this became the moment that the scales began to fall from Yousef’s eyes.

“We are living a lie and people are dying because of this lie,” he says. Later, Yousef reveals that he was raped as a child, but concealed it from his family out of shame.

Schirman is unconvinced that Yousef’s rape as a child or his witness to Hamas’s abuse of people in prison is sufficient alone to explain his repudiation of Islam, Hamas and his family.

“I think it’s many things. Mosab would talk to me about the rape off camera, but was hesitant to share it with us on camera because he was afraid, rightly so, that people would reduce his motivation to this,” he says.

“He’s intelligent with a very keen mind, and his motivation is made up of many things. It’s not black and white. The film is about two people who found their own moral compass, followed it, and went against the system.”

REPORT by Jan Epstein

PHOTO of Palestinian teenager Mosab Hassan Yousef a(left) and Shin Bet handler Gonen Ben-Itzhak in The Green Prince.

comments