Shmatte and South Melbourne: The Jewish market story

As the South Melbourne Market celebrates 150 years during May, Rebecca Davis explores the Jewish roles in the market’s story – a narrative underpinned by immigrant dreams.

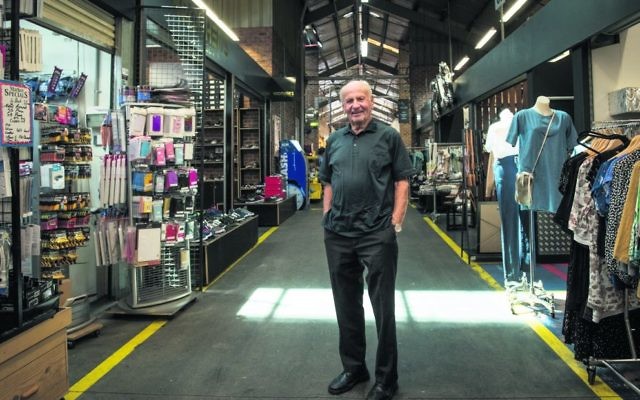

PAUL Millet attributes his salvation and success to “one very little word: luck”.

The 87-year-old sits poised on an autumn afternoon, outside a Caulfield South cafe. He peers out from behind his cup of tea in hand, black with a slice of lemon, pausing to reflect upon his 53 years as a stallholder at the South Melbourne Market – and before that.

Before that, was a world of strudel and symphony. What followed was a fortuitous series of events that saw Paul and his parents, Hermann and Sabine, dodge the Nazi menace that gripped Europe.

First, they fled from their home in Vienna to Milan, where they lived and hid for seven years. Then, they endured a long shipboard journey that would deliver them to the faraway waters of Port Phillip Bay in 1946.

Paul’s story is more than one of survival. It is one of resilience and tenacity, characteristics shared by many who left the ashy remains of post-war Europe behind them. They are qualities that would form the perfect propellent for entrepreneurship in their adopted land. Their achievements would write a new chapter of unheralded Australian-Jewish success, and in the process, etch out a legacy that continues today – in the shmatte (fashion) industry.

South Melbourne Market was instrumental in that narrative. This month marks the 150th anniversary of the market, a milestone that is being celebrated with the launch of the 150 Years of the Village Market exhibition.

The exhibition showcases the long and colourful history through the eyes of those who have known it best – the traders, shoppers and local residents. It features artefacts from the Port Phillip City Collection, historical information, film, memories, photos and stories.

Stories like that of Paul Millet.

When 16-year-old Paul arrived in Melbourne, he found work as presser in a coat factory on Flinders Lane. His older brother, Josef, came to Australia some years earlier. Travelling aboard the infamous HMT Dunera, the ship which brought German and Austrian Jewish internees on a harrowing journey from London to Australia, he was then interned at Hay, NSW.

Josef would later join the Australian Military Forces, before being issued a stall at the Queen Victoria Market. Despite not knowing a word of English, Josef and Paul’s parents took on the stall, selling socks.

“One Friday lunchtime – the factory used to close at 12 or one o’clock – I took the tram down Elizabeth Street to the Victoria Market,” remembers Paul.

“I didn’t realise that Victoria Market was such a big place! Well, I did find my parents. But I got stuck for the rest of my life in the markets!”

The following year, Paul’s father, Hermann, would also take on a stall at the South Melbourne Market. Shortly after, Paul would meet his future wife, Esther Pearl (known as Pearl) at a Habonim picnic. Once they were married, the decision was made that Paul would take over the South Melbourne stall, and Hermann would re-join his wife, back at the Queen Victoria Market.

The South Melbourne stall sold lingerie, nightgowns and women’s knitwear. Paul proudly asserts that everything he stocked had to be “high quality” and “Australian made”.

“Then we got in touch with Maglia, which was producing swimsuits, slacks and tops.”

Maglia of Melbourne were pioneers of the Australian fashion landscape. They used new fabrics such as Bri-nylon and Lycra to offer women increased support and shape. Maglia also embraced the modern concepts of an in-built bra, elasticised leg edging and a low scooped back in their swimwear, aiming to flatter all bodies. Paul became warmly known as the ‘Maglia Man’, as women would travel from across the city to be fitted by him.

The colour scheme, devised by Maglia’s owners – who were also European Jews – was completely new and exciting for Australians.

Jewish manufacturers produced goods that were sold into the hands of Jewish retailers. It was a common story.

“All the manufacturers that we bought from were Yiddishe people,” concurs Masha Fisher.

Masha arrived in Melbourne from Poland in 1939, with her parents David and Golda Abzac – just six months before the outbreak of World War II.

“My father brought with him his knowledge from his drapery shop in Warsaw,” explains Masha.

Upon settling into his new country, it was suggested that David seek a stall at the markets. In 1941, he became a stallholder at the South Melbourne and Dandenong Markets.

In addition his market career, David would become a cornerstone of the Jewish community: a writer for the Yiddishe Nayes (Yiddish section of The AJN), co-founder of Bialik College and board member of the United Jewish Overseas Relief Fund. He would also be instrumental in ensuring that Prime Minister Arthur Calwell increased the quota of postwar Jewish immigrants.

Masha worked with her father at South Melbourne, selling petticoats, half-slips and stockings for 9 shillings 11 pence.

She vividly recalls the Jewish stallholders that surrounded them. There was Mr Eisinger, who sold dress material to the left of their stall; Mr Havin, a seller of undergarments; Mr Gorey, the Polish Holocaust survivor, with his offering of jeans; Mr and Mrs John and Hannah Pitt, stockists of tobacco and cigarettes; Mr Erlich, the shoe peddler; Mr Millet, of course; and then there was “that Yiddishe man who had the cake stall.”

“He was there by himself most of the time. So, I would help him out if he needed. I would mind his stall so he could go to the bathroom, or get a coffee. We all spoke Yiddish. We all helped each other out,” says Masha.

Masha estimates around 80 per cent of the two rows of clothing stallholders were Jewish, a sentiment echoed by Paul Millet.

“If you went on Yom Kippur, you wouldn’t have found many stalls were open. Very few, but the fruit shops, the vegetables – they were Italians.”

Sophia Andrikopolous, co-curator of the 150 Years of the Village Market exhibition, reflects on the “very impressive” Jewish contribution to the market, “and indeed Melbourne”.

“Our Jewish stallholders brought with them new ideas and skills that had not been seen before at the Market,” she notes.

Aside from providing a livelihood for Holocaust survivors and immigrants, the South Melbourne Market also supported many applications for stalls from ex-prisoners of war.

Andrikopolous revealed a letter received from the ‘Ex-Prisoners of War and Relatives Association’ in 1948. The document implored the Market to allow “Mr Fisher of Clayton”, who suffered “for three years as a POW in Japanese hands”, to rent a stall to sell his flowers.

But the market atmosphere wasn’t always so inviting.

It was a microcosm of broader Australian society, and while it was not specifically anti-Semitic, Millet describes a pervasive anti-foreigner attitude. He remembers that he was often told to “go back to your own country”, and was publicly berated for not speaking English if overheard conversing in another language with his parents.

Despite such adversity, it is undoubtable that the South Melbourne Market was a beacon of hope, a cradle rehabilitating and nurturing scores of refugees and immigrants into new life, leaving their memories of pain to the past.

Paul arrived in Australia having evaded an obstacle course of peril. He had navigated a path home from school through the shattered glass of Kristallnacht. He had dodged denouncement; a neighbour exposing the Millet family while in hiding to an Italian Fascist commander who was known for his cruelty.

He had eluded the interrogation of Italian soldiers upon returning from a local farm, milk bounty in arm, by posing as a milkman on delivery rounds.

And when the Nazis were rapidly closing in on Milan, kind Italian Police issued a chilling warning to the Millet family: “the train to Auschwitz was ready”.

“But, you know, I didn’t come here to make money like most,” Paul admits, eyes twinkling as the rays of the afternoon sun wash across his face.

“But I succeeded to do everything I want,” he smiles warmly.

“That is all it is. Luck. If you don’t have luck – no good!”

The South Melbourne Market’s 150 Years of the The Village Market Exhibition is currently on at SO:ME Space, South Melbourne Market, until Wednesday, May 31 (Market days only – Wednesday-Sunday)

REBECCA DAVIS

comments