The high flying Jewish Anzac

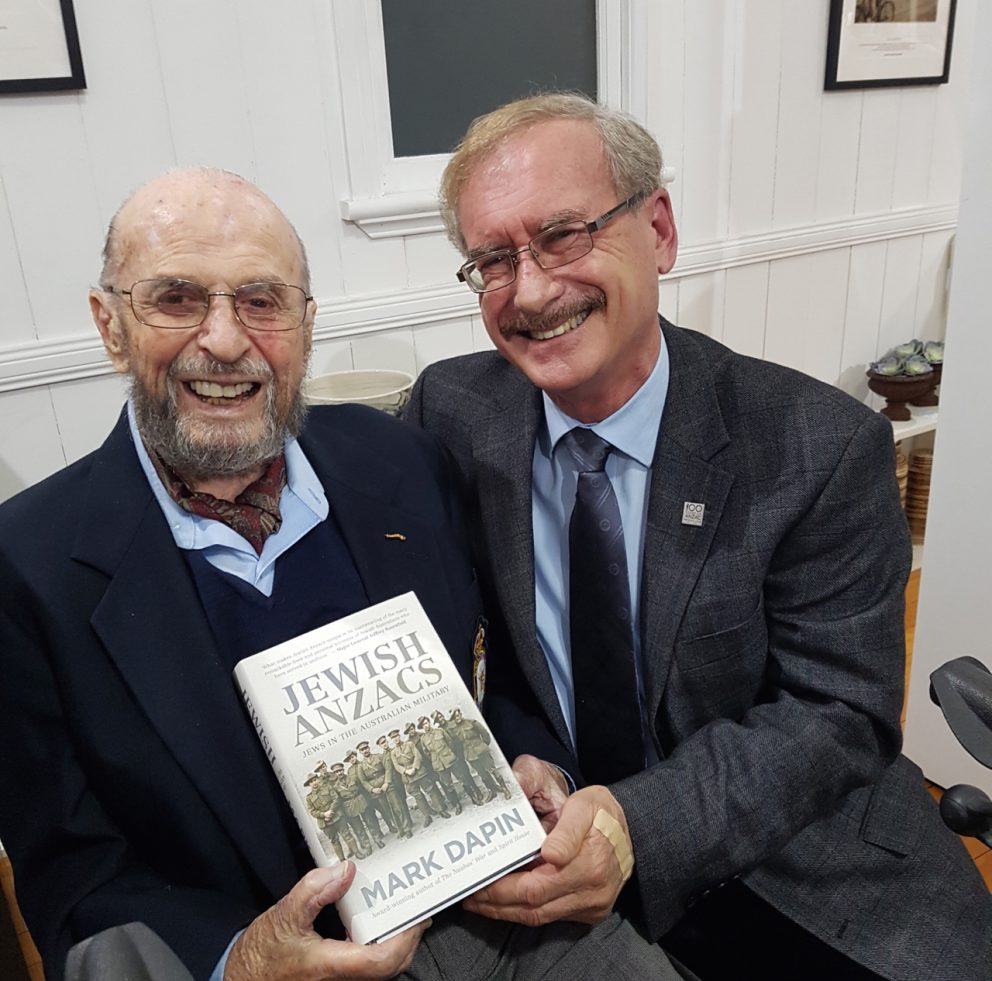

The dramatic true story of Cyril Borsht's experiences as a Lancaster bomber pilot on dangerous missions over Nazi-occupied Europe is just one of hundreds included in Mark Dapin's landmark book Jewish Anzacs.

THE dramatic true story of Cyril Borsht’s experiences as a Lancaster bomber pilot on dangerous missions over Nazi-occupied Europe is just one of hundreds included in Mark Dapin’s landmark book Jewish Anzacs. SHANE DESIATNIK was fortunate enough to interview Borsht before he passed away, aged 95, in Brisbane last November.

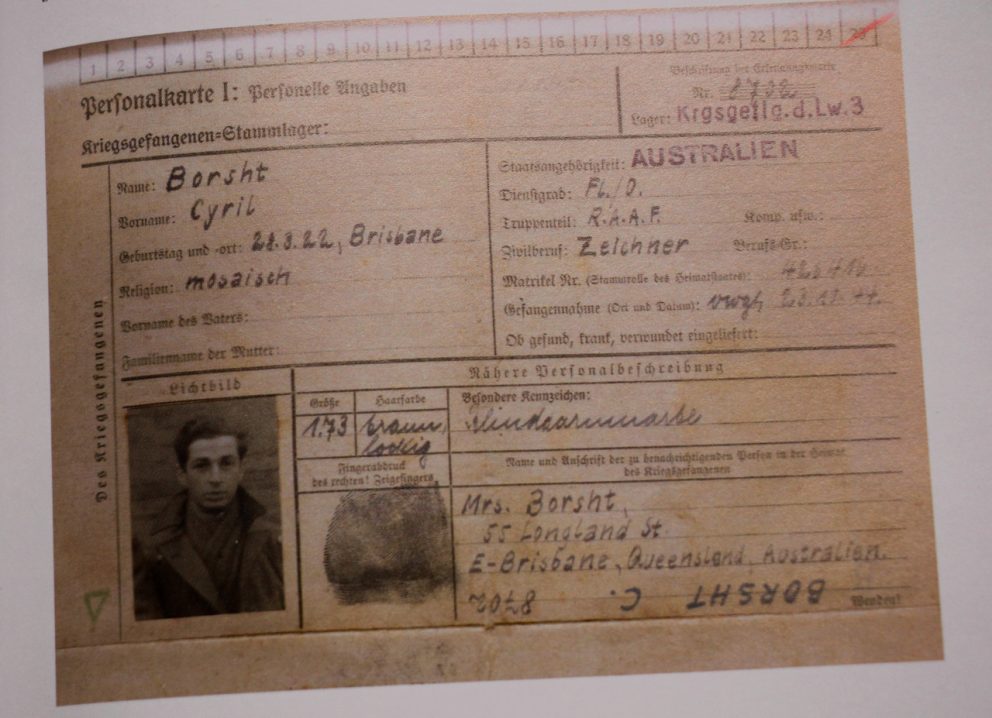

Like many young kids, Cyril Borsht grew up loving toy planes and dreaming of flying. So at barely 20-years-old, he didn’t hesitate to enlist with the Royal Australian Air Force in mid-1942.

If he was looking for drama, he certainly found it as a pilot in the Bomber Command based in England, from which he flew on countless hair-raising sorties and combined mass scale bombing raids across the North Sea, had several near misses, and ultimately got shot out of the sky over Holland, spending the last eight months of the war as a POW in Germany.

For his efforts in executing successful missions over Le Havre, Brest and Boulogne, Borsht was one of 10 RAAF pilots to be awarded a Legion of Honour by the French in May 2016.

Yet humbleness was the first quality I noticed about Borsht when I phoned to interview him.

“You want to interview me . . . really?” he asked, surprised.

“There’s so much in Dapin’s book – it’s an important one that’s been waiting to be written.

“In all fairness, I’m just a very small part of the bigger picture.”

The next quality was passion.

“I reckon the Lancasters were the best planes in the war – they did most of the night time bombing over Europe and were probably the aircraft most responsible for shortening the war”.

“They were brilliant to fly – they had four engines, but could fly on two, which proved very handy – especially during one mission when two of our engines blew up!”

In Jewish Anzacs, Borsht describes flying to and returning from “horrible places” and the chaos and risk involved during bombing missions involving hundreds of planes converging on the same area, with German Messerschmitts spraying bullets at them at any opportunity.

“I suppose at that age, early 20s, there’s a certain amount of bravado, and you just don’t think you are going to be shot down, or think far enough that you might be captured by the Gestapo,” he said.

On October 23, 1944 his plane was shot down over Holland, and he helped a fatally wounded crewman parachute out with him at 900 feet rather than allow him to die alone.

Fortunately, two other crewmen survived, but all were captured by the Germans and spent the remainder in the war at several prisons in Germany, including Sagan Stalag Luft III, made famous in the movie The Great Escape.

“I was suddenly confronted with the fact that I was a Jewish POW in Germany, so I had certain aspects of terror and fear added to my initial experience.

“We were placed in solitary confinement for four days and I was interrogated by a German officer who discussed my Jewishness and used it as a threat to try to gain information from me – but it was information he already knew, and he just wanted confirmation.”

Things got better for Borsht when moved again.

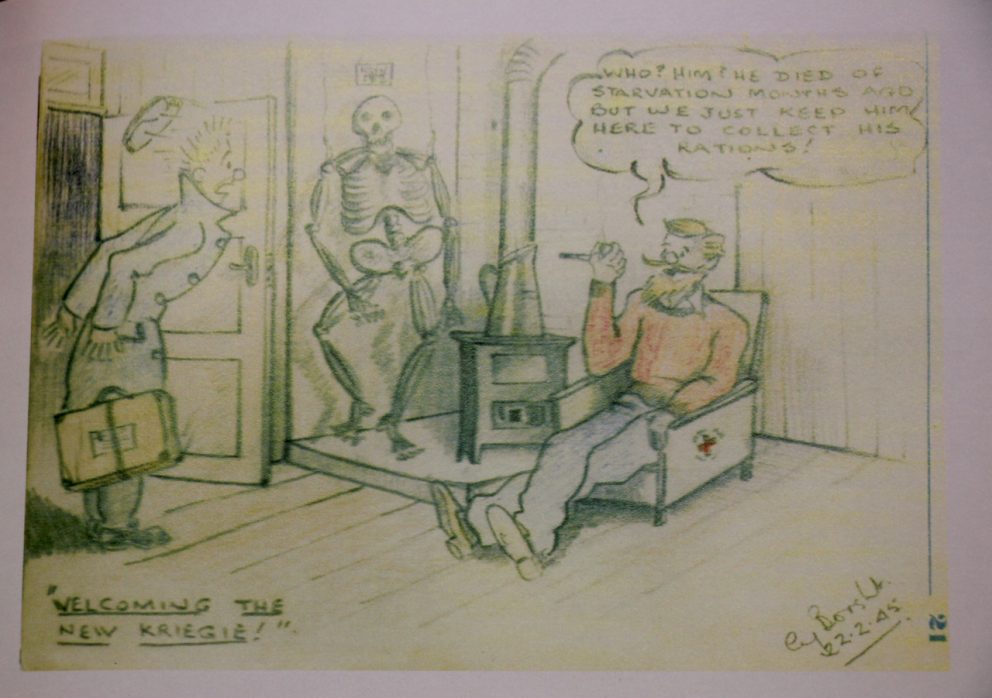

“The German army had this crazy attitude [obsessiveness] to rank, so POWs who were officers, which I was, were not allowed to do any work, so we had all this time on our hands, which you had to fill somehow.

“I liked to draw, so I filled a Red Cross log book up with cheeky cartoons and drawings.

“We were 18 [POWs] per room, all in three-tiered bunk beds, so you really got to know each other very well.

“I became friends with a Jewish POW from Wigan [UK], flight officer Harry Lanzetter, and we kept corresponding with each other well after the war, right up until he passed away.

“I think what saved me – us – was it was late in the war, and the Germans were running scared.”

Borsht’s son, Peter, told me he has proudly kept his late father’s wartime documents, including his sketchbooks as a POW, all this time.

One of his cartoons is featured in Jewish Anzacs.

During the research and writing process, Dapin said he felt it was important as far as he possibly could to “work off personal accounts like diaries and letters – of servicemen and women, of soldiers and nurses who’d left testimonies – to include their own words.”

A most comprehensive book, Jewish Anzacs has a list of 6,798 Australian Jewish servicemen and women, a memorial roll with 342 names and cemetery details.

There are many first-hand accounts of incredible scenes, from soldiers observing Jewish festivals in Egypt, Libya, Gallipoli and Palestine, to harrowing descriptions of landing under heavy fire at Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, the horrors of trench warfare on the Western Front, the triumph of being a part of the famous Charge of Beersheba, and heartbreaking letters sent home by teenage soldiers, some of whom were killed in action within days of writing them.

Other Jewish RAAF pilots featured in the book include Distinguished Flying Cross recipient Peter Isaacson, who flew 45 missions over Europe in Bomber Command, and Joe Barrington who completed 52 missions, and brothers Sol Levitus and Maurice Morris, who both, tragically, did not survive the war.

Dapin said when researching the book he was surprised at just how much material there was available about Jewish Anzacs who served in the 20th Century right up to the present – “far more than I’d initially envisaged”.

“And there are more Jewish men and women in the Australian Army, Navy and Air Force, now, than I think most people are aware of,” he added, at last year’s Sydney Jewish Writers’ Festival.

“It’s incredible to think, for example, that there were three other Australian Jews [serving] at the same point in the Afghanistan war when Private Greg Sher was tragically killed in action [on January 4, 2009]– in the same small outpost in the middle of the desert – and that’s what we know of – there were probably more.”

Rabbi Yossi Friedman – who serves as Jewish chaplain for the RAAF – agrees.

In commending Dapin for the invaluable resource that Jewish Anzacs is, he said “I estimate the number of Jewish Australians currently serving in the Australian Defence Force to be about 400”.

“That represents about 0.4 per cent of total ADF personnel – roughly the same proportion as the number of Jewish people within the Australian population – quite a significant contribution by any standard.”

Along with commemorating the selfless service and sacrifices of Jewish Anzacs of the past, that’s another important aspect to reflect upon, and take pride in, during a week dominated by Anzac Day.

Jewish Anzacs by Mark Dapin was published by the Sydney Jewish Museum and New South Publishing on April 1, 2017 and is available at the museum and at leading bookshops.

comments