Trials and tribulations of the Jewish people

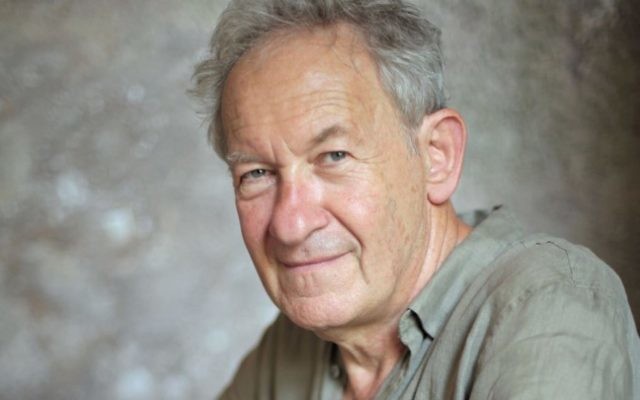

Through waves of persecution, expulsion and forced conversion, the Jewish people remain defiant against all odds. Simon Schama addressed the Sydney Writers’ Festival and spoke to Sophie Deutsch about his book, The Story of the Jews: Belonging earlier this month.

Through waves of persecution, expulsion and forced conversion, the Jewish people remain defiant against all odds. Simon Schama addressed the Sydney Writers’ Festival and spoke to Sophie Deutsch about his book, The Story of the Jews: Belonging earlier this month.

WRITING on the Alhambra Decree of 1492 in his acclaimed book, The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words, British historian Simon Schama quotes a priest, Andres Bernaldez.

“They went along the roads and over the fields … in much travail and misfortune, some falling, others standing up, some dying, others being born, others still falling sick, and there was not a Christian who did not feel sorrow for them and wherever they went they [the Christians] beseeched them to be baptised and some in their misery would convert and remain, but few, very few did so, and the rabbis continually gave them strength and bade the women and girls sing and play tambourines and timbrels to raise the people’s spirits.”

Spilling out from Spain in their thousands, many Jews refused to leave behind their faith in the hostile land from which they fled.

Schama poetically terms the inspiring, peculiar spectacle as the “heroism of the displaced”.

Speaking at the Sydney Writers’ Festival (SWF) earlier this month in conversation with historian Paul Holdengräber, Schama, a professor of art history and history at Columbia University remarked, “It was a startling and powerful memo when the heroism of how you conduct yourself obstinately suddenly strikes those who are doing the intimidation as almost intrinsically, almost inconceivably noble, or in some cases, inconceivably obtuse.”

Many of those who did convert, ostensibly remaining Christian by marrying in churches and baptising their children, remained devotedly Jewish behind closed doors, often seeking secret passage to a freer and more tolerant land.

“There was an underground railroad conveying new Christians who wanted to revert to Judaism to the one place they could, which was Ottoman Turkey, which was much more welcoming to different kinds,” Schama commented. “What was truly extraordinary was that this underground railroad began in Portugal on the Tagus River [and] went to London where there was an underground Jewish community. Shakespeare may have indeed known them. And it was funded by the most powerful and wealthiest new Christians, a family in Antwerp.”

Caught in an impasse, so-called new Christians were rarely spared from scrutiny but became the unfortunate target of the Spanish Inquisition.

Asked by The AJN how he evokes hope in readers when Jewish history is fraught with antisemitism, persecution and a constant battle for acceptance, Schama conveyed it is difficult not to present a doom and gloom situation, noting that the next volume of his series – when he tackles the Holocaust and the subsequent founding of the State of Israel – will present particular challenges in this regard.

As a Jewish historian, Schama’s series on the The Story of the Jews, which has been turned into a successful BBC series presented by Schama himself, raises the question which Holdengräber posed, why call the series a story rather than history?

“One of the themes of the book is how to make the story of the Jews the story of everyone,” Schama answered. “On the one hand, you don’t want to dilute the particularities of the experiences you’ve gone through, good or bad, but on the other hand … the struggle we are having with Holocaust education now is not to jump in a vulgar, contemporary way. That it seems something peculiar and unique and only happening then and therefore an exception.”

Unravelling the detailed narratives of individual stories against a broader historical backdrop in The Story of the Jews: Belonging, Schama evokes in his readers empathy for the struggles of the common man and king alike, ensuring the individual impact of mass historical events is deeply understood.

As writer Andrew Anthony penned in his review of Schama’s book published in The Guardian in 2017, “History, you learn, is what happens to you when you’re busy trying to survive.”

Although Schama’s compelling stories imbue history with his own colourful flair, he remains devoted to the historian’s craft, drawing inspiration from those who came often well before his time.

“Herodotus was at least as interested in the Persians and the Egyptians” as he was in the Athenians, said Schama, describing Herodotus’ approach as “more gossipy or heterogeneous, more travelling”, and influencing the course of Schama’s own historical work.

“When I started working on Dutch history or on French history, my sense was it’s actually in the most challenging and powerful commitment you could make was living inside the life of those separated from you in time and place,” Schama said.

It is a natural consequence then, that Schama’s second volume deals with a 16th century conman in Venice, a boxer in Georgian England and a general in Ming China.

Such detailed portrayals of figures throughout history feed into Schama’s recently published book, Wordy, which he also discussed at the SWF.

In a comprehensive compilation of Schama’s self-professed best essays, Wordy covers diverse figures including Sir John Falstaff and Johannes Vermeer.

Admired for his remarkable command of the English language, Schama, in speaking to The AJN, insisted there is no set formula or series of principles for excellent writing, but each author should develop their own style and seek inspiration from their literary models.

For Schama, that is not only Herodotus but also James Joyce and Victor Hugo.

No doubt Schama’s own methodical yet mesmerising historical mode will shape the work of writers for generations to come.

comments