‘I want an apology before I die’

More than seven decades after his liberation, Holocaust survivor Eddy Boas has written his memoirs. He shares his story with Yael Brender.

More than seven decades after his liberation, Holocaust survivor Eddy Boas has written his memoirs. He shares his story with Yael Brender.

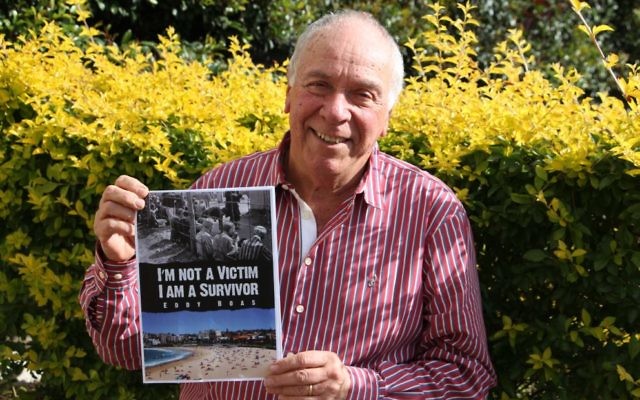

“We are the only family that went into the camps together and came out together,” says Eddy Boas, one of the youngest Jewish survivors of the Holocaust and author of I Am Not A Victim, I Am A Survivor, published this month.

Born in The Hague, Holland, in 1940, Eddy was three months old when the Nazis invaded and three years old when his family was rounded up and sent to Hollands Spoor train station. From there, he was loaded into a cattle wagon with his mother Sara, his father Philip and older brother Samuel, who everybody called “Boy”. They were deported to Westerbork concentration camp where they were kept in the largest barrack.

In 1944, the family was transported in a cattle wagon to Bergen-Belsen. They were kept in Star Camp, along with 6000 other prisoners who had been designated for possible exchange with German prisoners of war. Philip, a former soldier from the mounted division of the Dutch army, was selected to care for the horses in the camp and to move the bodies of deceased prisoners.

“That gave him an opportunity to steal food from the horses and give to us,” Eddy explains. “My brother would follow him around the camp as he was picking up bodies. My father would stand next to a horse, and at the same time, people would come up to the cart to look at the bodies to see if they knew anyone.

“My brother would crawl through the crowd and my father would drop a potato or a turnip and a carrot onto the ground, and my brother would pick them up, crawl back and run to my mother … That’s how we managed to get extra food. And that is part of how we survived, because food in Bergen-Belsen was very scarce, especially towards the end.”

On April 8, 1945, as the British advanced, the Star Camp prisoners were divided into three groups and were loaded onto trains bound for Theresienstadt in then-Czechoslovakia. But the train with Eddy’s family – the third train – was forced to take a long, tortuous route back and forth between the Russian and German front lines due to Allied bombing of the railway line. It became known as “the lost transport”.

“My mother jumped off the train somewhere along the trip, and stole seven potatoes,” Eddy recalls. “When she got back, the train had left. She had to hitch a ride on a horse and cart along the train line and she came across two trains, the Hungarian one and our one. She called out Philip’s name and found us … My parents’ will to live, their determination to save their children, got us through everything.”

The train was eventually liberated by the Red Army near the German village of Troebitz. Many families, including the Boases, were put up in an empty school. When Eddy started showing signs of having typhus, the Russians helped the family move to Riesa, 80km from Leipzig, where Philip and Boy stole food for the family.

“Eventually, my father had enough of Riesa,” Eddy explains. “Nobody was coming for us. Nobody was helping us get back to Holland. My father took matters into his own hands … We hitched a ride in a Russian soldier’s Jeep for the four of us as far as the banks of the River Elbe. We were exchanged for six gypsies – the Americans on the Western side of the river sent the gypsies east and brought us to the west, to Leipzig.”

One day when Boy was out begging, he came across Captain Douglas, an English soldier who took pity on the family and brought Eddy to the army hospital where he was given medicine to cure his typhus. When he had recovered, Douglas arranged for the entire family to return to Holland by train. They arrived back in Holland on June 13, 51 days after leaving Bergen-Belsen.

“But we had nowhere to stay. My parents first went to their old house, and the people who lived there told them to get lost. So they went to the police, who told them to get lost. So they went to the Hague City Council who weren’t interested, but they found a convent in the Hague to take us in … Finally, we found a distant relative to take us in, and then life became normal. That’s the first time I was in a real home.”

But life wasn’t much easier in the aftermath of the war. In 1947, Eddy’s parents had another child, Estelle, “which brought joy to our lives for the first time”, and planned to emigrate to Australia. But Philip died of stress-induced heart failure in 1948, and their plans were put on hold.

Finally, in 1954, the family arrived in Australia. They rented a flat in Coogee, Sara went to work as a cleaning lady at the Coogee Bay Hotel and Eddy was enrolled in South Sydney Technical College before leaving at age 15 to work at the radio station 2CH. But Boy could not adapt to his new surroundings.

“My brother suffered very badly from life in Bergen-Belsen,” Eddy says. “He’s 82 now, and he still has nightmares every single night. In his younger days, he knew only one way to survive and that was to steal … So he kept getting in trouble with the Australian police.”

Boy moved back to Holland in 1959, where he ran into trouble with the Dutch police for the same reason. He was arrested for a variety of minor crimes, and put in gaol in Breda.

In the cell next to him was Nazi SS captain Ferdinand Hugo aus der Fünten, who was directly responsible for the deportation of 80,000 Dutch Jews. In the next cell was Gestapo officer Franz Fischer, who had been in charge of the deportation of 18,000 Jews from The Hague.

“I’m pretty disgusted with the Dutch government,” Eddy says, and their treatment of his brother is not the only reason.

“To this day, the Dutch government has not apologised to any Jewish organisation or survivor for the way they treated Dutch Jews during and after the war. Every single Western European country has apologised in some way, but the Dutch have not.

“My aim, before I kick the bucket, is to get an apology from the Dutch government.”

In 2002, at his wife’s urging, Eddy decided to write his memoirs after a triple heart bypass. But there were gaps in his story, so he reached out to the Dutch government to find out what had happened to the rest of his family. One of his enquiries was about insurance policies that his family members had taken out before the war.

“To this day, there are millions of Euros still in the possession of banks and insurance companies that belong to Jewish families,” Eddy explains.

“The Stichting-SJOA [the organisation set up to handle outstanding entitlements] said they would look into it and I heard nothing back for a year. I contacted them again, and then finally, months later, they got back in touch and said neither me nor my brother were entitled to the insurance taken out before the war.”

As early as 1946, Eddy’s parents had made efforts to claim back or be compensated for the missing assets of their parents, brothers and sisters, all of whom had been murdered in concentration camps. They were denied.

The reason they were given was that under Dutch law, the beneficiary of the insurance is the last person to be alive. For instance, Eddy’s aunt – his mother’s sister – and uncle had a policy, and both were murdered in Auschwitz. Because his aunt was apparently murdered first, the descendants from his uncle’s side of the family were entitled to the proceeds. This happened with all three of Sara’s sisters, and in all three cases, the husband was deemed to have died last.

“I wrote back to them saying how do you know who died last?” Eddy said. “Their answer was that a committee of bureaucrats decided based on a formula that they established.”

Eddy questioned the accuracy of the recorded dates of their murder, and was sent a letter that read, “The accuracy of the dates of death is questionable indeed … Of course there were no official records kept by the Nazis … The Dutch Red Cross first tried to reconstruct the possible date of death by information of witnesses [and] deportation lists.”

He lives his life by a simple philosophy: I can’t do much about what happened yesterday, and I can’t make plans for tomorrow and thereafter but I can control today.

“I have no hate but I do believe that the Dutch government owes me an apology, and a lot of other people, for the way they treated my family and I can still do that today. To this day, I have never received any compensation from either the Dutch or German government for the sufferings I endured as a three- to five-year-old child, forced to spend 655 days locked up in concentration camps and on a lost Nazi train.”

According to the Dutch and German governments, being locked up and deprived of freedom for no legal reason, as an innocent child, does not entitle Eddy to claim compensation. And he is determined to spend the rest of his life righting that wrong.

“No money will ever be able to compensate for what I had to endure, but an acknowledgement of wrongdoing would go a long way.”

YAEL BRENDER

I Am Not A Victim, I Am A Survivor is available for purchase at the Sydney Jewish Museum.

comments